Surely by now you’ve heard the news about the $25 million Operation Varsity Blues bust, in which dozens of wealthy parents and coaches have been arrested for scamming the private university entrance system in the most egregious ways. If not…welcome to the internet! Hope you like it here. Enjoy your stay, don’t click links to “Which Beatle are You?” quizzes, and don’t read the YouTube comments.

Of course this university scam has captured our collective attention; it’s one of those near universal outrage stories in which everyone can participate. Everyone is horrified. Everyone has something to say about it.

Few are shocked in the least.

There’s so much great discussion right now about the myriad “legal” ways that the uber wealthy have always been able to get less qualified kids access to top universities. (CoughJared Kushnerahem.) There’s discussion about how this scandal shines a light on the need for affirmative action. There’s discussion about how even upper-middle class parents — and particularly white parents — have always had certain advantages, including legacy admissions, access to top-performing high schools in high-income zip codes that feed top-tier colleges, the money to send a student on that high school science expedition to the Galapagos that ends up being her get-into-college-no-problem admissions essay.

Even simply having resources to hire test tutors has meaningful impact.

(I remember my mom scrounging to afford a mere four tutoring sessions in the final weeks before my own SATs. The tutor said, “I don’t know how much I can do for you.” I believe got through “G” on the vocabulary list. I still wonder what my Verbal score might have been should we have made it to at least the “R” words.)

However one topic I’m not seeing a lot of just yet: the fact that as parents, we are now expected to be wildly involved in our kids’ educations, to help them get the best grades, the highest test scores, and the most extraordinary extracurricular successes, in order to give them the most opportunity in life.

We simply can’t all do everything. And some of us can do far less than others.

That’s a problem.

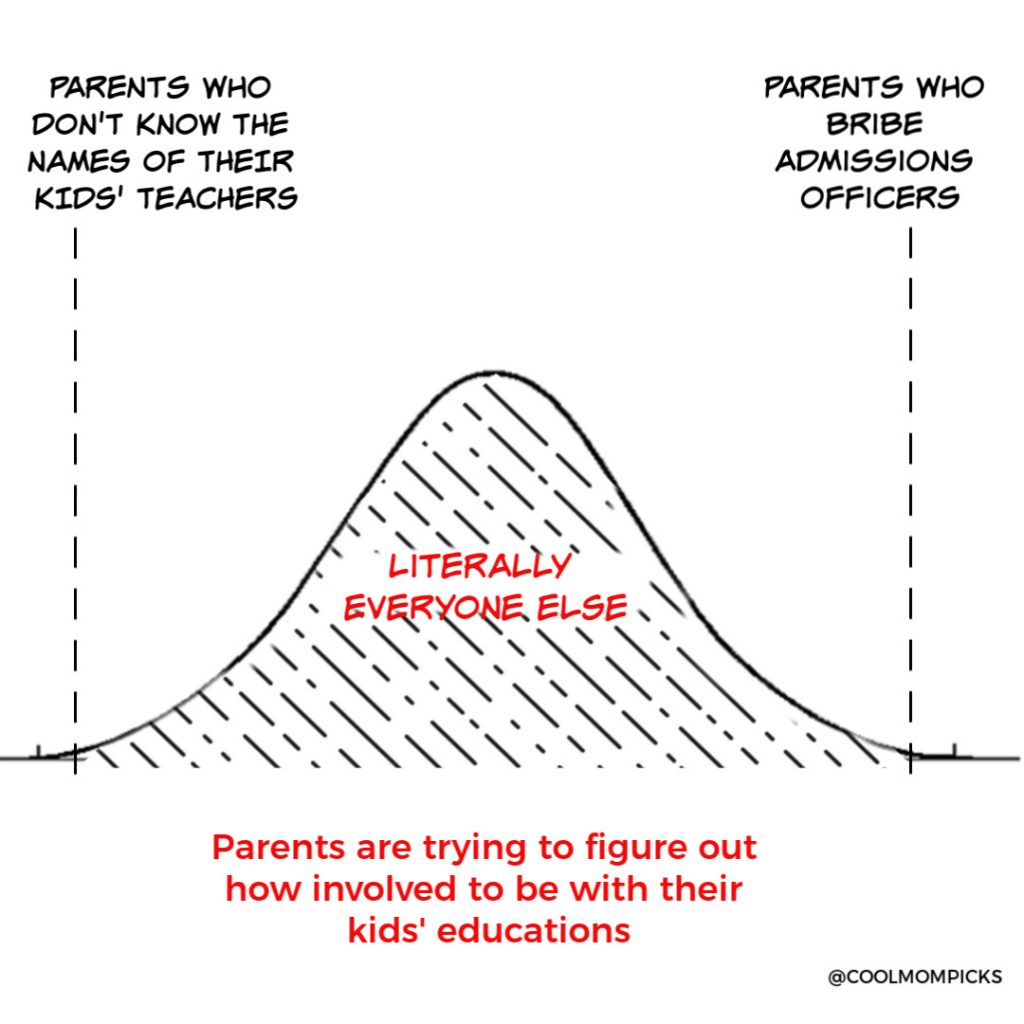

Okay, so let’s say we’ve got a spectrum of parental help — a bell curve. On the far right, we’ve got: bribe a fake foundation (then claim it as a charitable deduction), fabricate test scores, and photoshop photos of students onto other student athletes to magically turn our non-athlete into a soccer prodigy.

On the far left, we’ve got parents who have never once looked at their child’s report card and don’t have education high on the priority list for whatever reason.

As with all bell curves, the majority of us fall somewhere in between. And we’re struggling.

Did you give your entering preschooler just a weeeeee bit of design help in putting together the requisite “this is me!” collage for the first day of class? (Judging from my own kids’ preschool experiences, about 75% of you should be nodding. Yeah, you with the hot glue gun…I see you.)

Now consider the fact that this kind of help requires a few things: Artistic ability, craft supplies, probably a computer printer at home (with ink), and above all, time.

Yes, we can all rebut this idea by talking about lifting ourselves up by our bootstraps and finding printers at public libraries, about “where there’s a will there’s a way” and so on, and sure that’s true to some degree — but really. Come on.

What I’m hoping is that his story has more of us thinking about and acknowledging which other ways we have (or haven’t) been able to get involved with our children’s education, and the varying degrees of privilege that are required for each of them, so we can see if we can fix the system in just and positive ways.

For example:

Are you able to take your kid to the aquarium when they’re studying the skeletal system of fish? Watch the Ken Burns Civil War documentary with them on Netflix when they’re studying Reconstruction? Fill your home with books that bring to life the subjects your kids love?

Have you homeschooled? Or considered that it could even be a possibility?

Have you been able to take a day off of work to chaperone a class trip?

Have you paid for a subscription to an educational app of any kind?

Have you been able to participate in PTA meetings, curriculum nights, or school events — and if so, do you notice that there’s often a dearth of single parents, or those who live farther from the school, or parents who are working two out-of-home jobs?

Can you take the time to correct (and understand) math homework? Confirm your kids have read the 20 requires pages before you sign off on the reading log? Read over their essays closely enough to correct typos, and suggest that maybe “bullfrog’s” shouldn’t have an apostrophe since it’s a plural noun and OMG you are going to drive me crazy with this already? (Okay, so that’s me.)

Have you run for PTA office or spent the hours it takes each week to chair a school committee, which happens to give you more access to teachers, administrators, and a network of other parents? And by the way — bless those volunteering parents, who are essential to our schools’ successes.

Channey via Unsplash

Can you afford the time and money it takes to get a kid to regular tennis lessons/ ski lessons / diving lessons / soccer practice / hockey practice / basketball practice / computer club / play rehearsal / ballet recitals / orchestra lessons which could end up factoring into a college admission decision? Are you able to show up for the performances and games and matches as a way to show your support for your child’s passion?

And finally, are you scrambling to pay for tutors or find other help to help raise your kids’ test scores or GPA because those numbers become absurdly important, even to the exclusion of other outstanding attributes of our children?

What more would we all do for our kids — without committing felonies — if we could, and how would it help them?

We all probably have something on our list. Because that’s the system we’re all stuck in right now.

————

Kristen and I discussed whether this entire scandal was a case of helicopter parenting gone mad. But it seems to be more a story about privilege and entitlement.

I think it’s also about using privilege in an educational system that’s always been built to reward it.

Having gone through the hell that is the NYC public high school application process this past fall for my daughter who wants to pursue performing arts, it was nothing short of another full-time job. I had to help her research dozens of school. I had to set calendar alarms so I could log onto a website the second a slot in a rare tour opened up. (Other parents even paid $200 for a helpful service that would alert you to new open house opportunities to give you an early shot at landing a spot.) I took time off during the school day to attend said tours. I attended as many as three to four open houses in a week week across three boroughs. I accompanied my daughter on auditions, sometimes dedicating entire weekend days starting at 6AM to hang out in a school cafeteria during those auditions. I had to find the money to pay for some acting and vocal coaching. And we weren’t even applying to NYC’s Specialized High Schools, which require a whole other level of tutoring and test prep and interviews and tours.

Ben Mullins via Unsplash

All that time, despite the sacrifices I was making to be there, I kept thinking that I was so fortunate that I could figure out how to do as much as I did do, and how lucky I was to have a job that offered flexibility, nd nearby family and friends I could lean on for childcare and other support.

That is privilege right there. And we are talking about public high school.

————

I hope this all leads to more conversations about how to fix this system, and how to make the best opportunities more equitable for all kids. I hope we talk more about how grades and test scores and “teaching to the test” and name-brand university educations have become important to the point of absurdity. I know we’re going to talk about the big picture of access, including affirmative action, legacy admissions, and the ways the uber-rich and connected have always lived their lives by different rules than the rest of us.

But I especially hope it opens more parents’ eyes to the idea that some of the so-called basic things we do for our kids, some of which we middle-class parents take for granted, we shouldn’t take for granted at all.

I have the distinct recollection of a “liberal” white parent in my child’s public school once complaining during an evening meeting, “it’s the same parents here all the time.” The implication was that the “problem kids” did not have parents who cared enough to attend. The racist and classist undertones of the statement were unmistakable, and other parents visibly bristled.

But I wonder how many had been thinking the same thing to themselves.

Look, we’re not all Melons. We’re all just doing the best we can as parents. Let’s fight for an educational system that’s the best it can be, too.