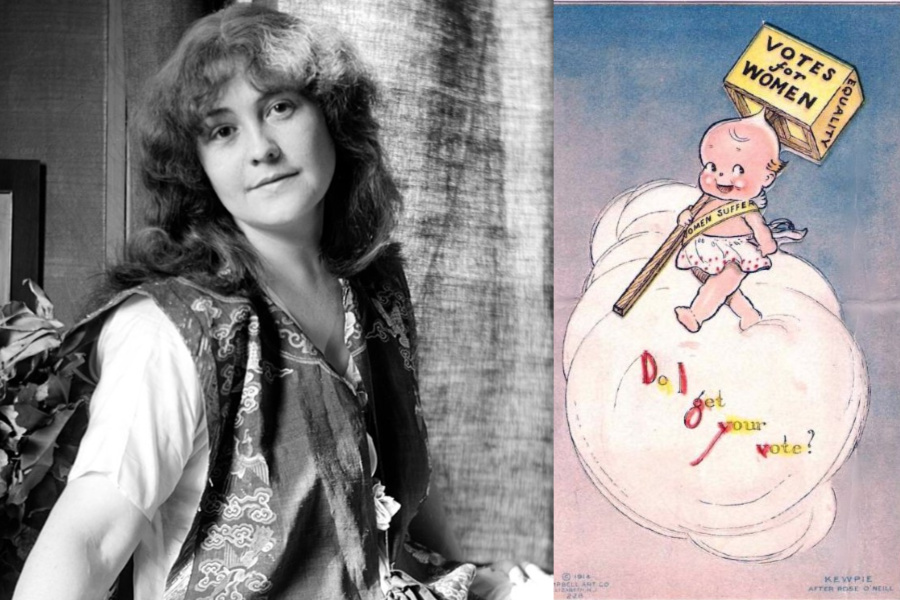

Next in our series of untold American Women’s History Month stories our kids will love, I kind of went down an awesome rabbit hole learning about the history of women’s political cartoonists and comic writers and illustrators. That’s when I discovered the wonderful story of Rose O’Neil, which I never knew at all.

If you’ve ever heard of a Kewpie doll, well, that’s because Rose invented them.

Related: 6 new biographies of great American women you don’t want to miss this Women’s History Month

As the only female editorial cartoonist on staff at the humor magazine Puck starting in the late 19th century — and in fact, the only woman at all on staff at Puck — Rose honed her art nouveau style illustrations, creating political cartoons, illustrations, and magazine covers about major issues of the day, at a time that women weren’t generally talking about politics in polite society.

She was already popular, but in 1909, she gained a truly huge following for introducing her adorable Kewpie characters in Ladies’ Home Journal. In fact, by many accounts, they were the best-known cartoon characters in the world until Mickey Mouse came along and that’s saying something.

Smithsonian Magazine has a fabulous article about Rose O’Neil, which describes not only how she made a fortune as a savvy marketer, turning her characters into patented dolls (loooong before Barbie but just before Raggedy Ann) and lending their likeness to brands.

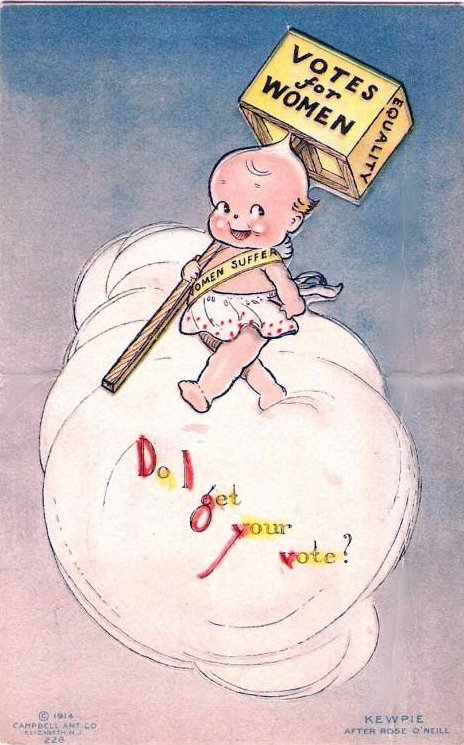

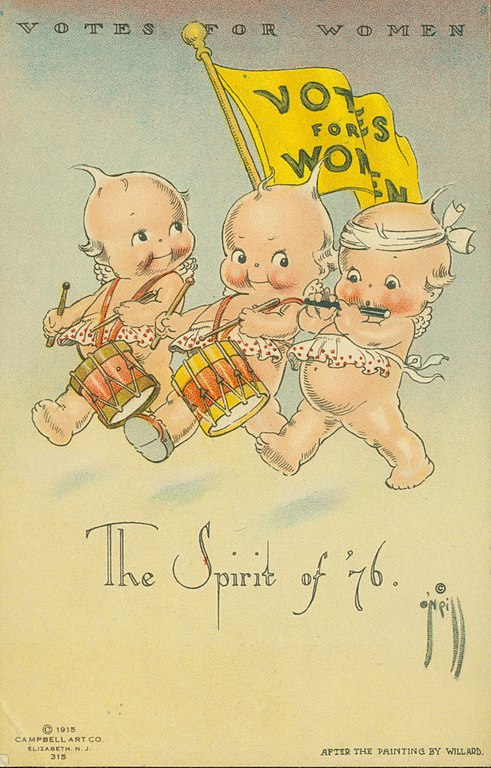

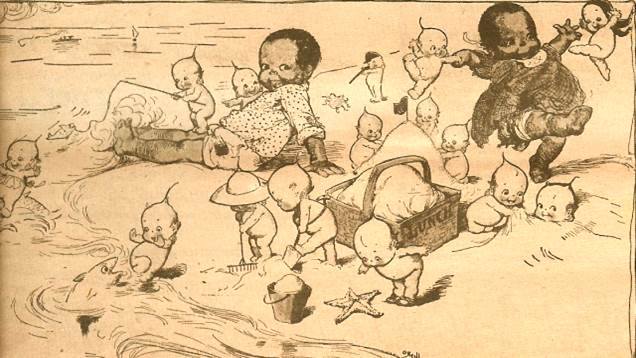

But what’s really interesting is how Rose cleverly parlayed the Kewpie’s popularity into cartoons about social issues she cared about: In particular, racial equality, economic justice, and women’s suffrage.

Related: Beyond Wonder Woman: 14 empowering girl Halloween costumes inspired by real life heroes

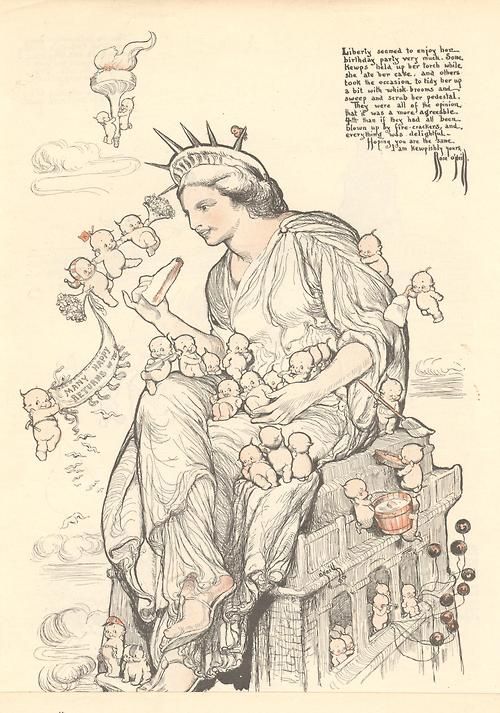

Rose O’Neill’s Kewpie postcards promoting women’s suffrage

It was a brilliant move; by using beloved, innocent babies to get the word out about charged political issues, she was able to reach a large audience that may not have otherwise been that engaged with them.

In addition to women’s suffrage, she took on issues like segregation and racial disparities, including tough topics like the lynching epidemic in the south. Rose was also among the first cartoon artists to depict Black people without hurtful, stereotypically exaggerated features. (Or at least, no more than she drew her white people, from what I can tell.)

via the Rose O’Neill and Bonniebrook Museum Facebook page

Did all of this social and political advocacy hurt her career? Not at all. By 1914, no woman illustrator was more successful or more highly paid. In 1917, she was admitted to the all-male Society of Illustrators in New York City. And by 1920 — well, the 19th amendment was ratified.

If you or your kids want to know more about Rose O’Neill, you can still track down her memoir, The Story of Rose O’Neill: An Autobiography (from our affiliate Amazon, or used and vintage booksellers); and the State Historical Society of Missourians has a very good bibliography including articles, books, and online resources. You can even visit the Rose O’Neill Museum in Springfield, MO, which was built by her great-nephew David O’Neill. Cool!

Also worth reading: Smithsonian Magazine’s article about women political cartoonists of the 19th and early 20th century. Everyone knows about Rube Goldberg, and maybe Thomas Nast — but there are quite a few women who’ve earned their place in cartoonist history, too.