Last night’s 2019’s Best Picture award at the Oscars went to Green Book, a film based (ever so loosely) on a real relationship between prominent Black jazz pianist and classically trained musician Dr. Don Shirley, and his hired driver, Frank “Tony Lip” Vallelonga, an Italian-American club bouncer who accompanies Dr. Shirley on a 1962 concert tour across the south.

It’s been met with an incredibly polarized response, to say the least.

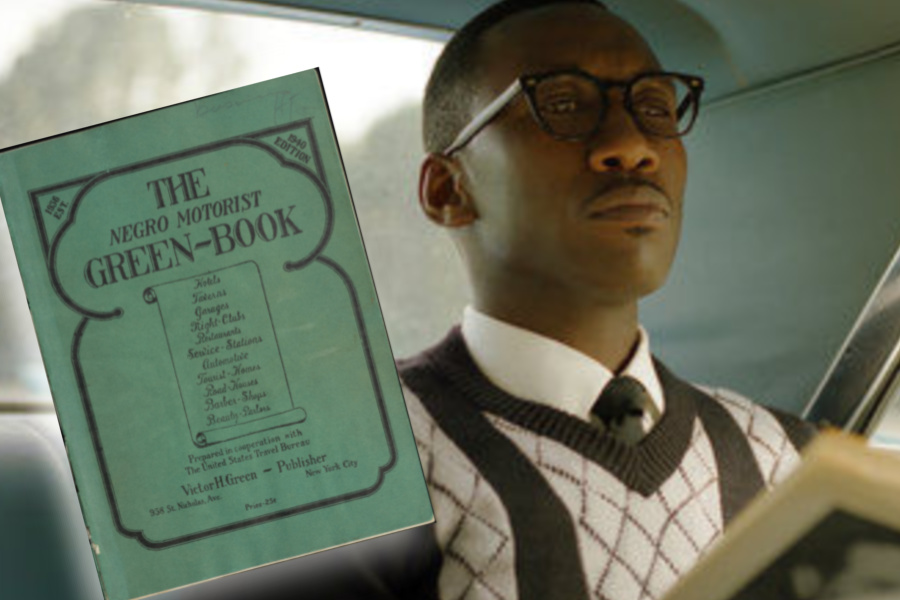

While I thought the performances were outstanding (props to Mahershala Ali’s well-deserved Best Supporting Actor win, though in the not-Hollywood-award-shows world, it was not a really a “supporting” performance), the film has some…problems. As you might have heard.

In particular, they’re problems that a lot of white people seem to be having trouble seeing. And as a white woman myself, I have found it incredibly helpful to read more perspectives and analyses of the film, especially from writers of color.

I love having discussions with my kids about the real stories behind historical fiction and biographical films, and if you’re like me, I think it’s worthwhile to read some of these articles to help guide the conversation and give you additional frames of reference.

Related: Where to stream the 2019 Oscar nominated movies, and which ones to watch with your kids

Articles about the Green Book controversy that are worth a read

New York Public Library

New York Public Library

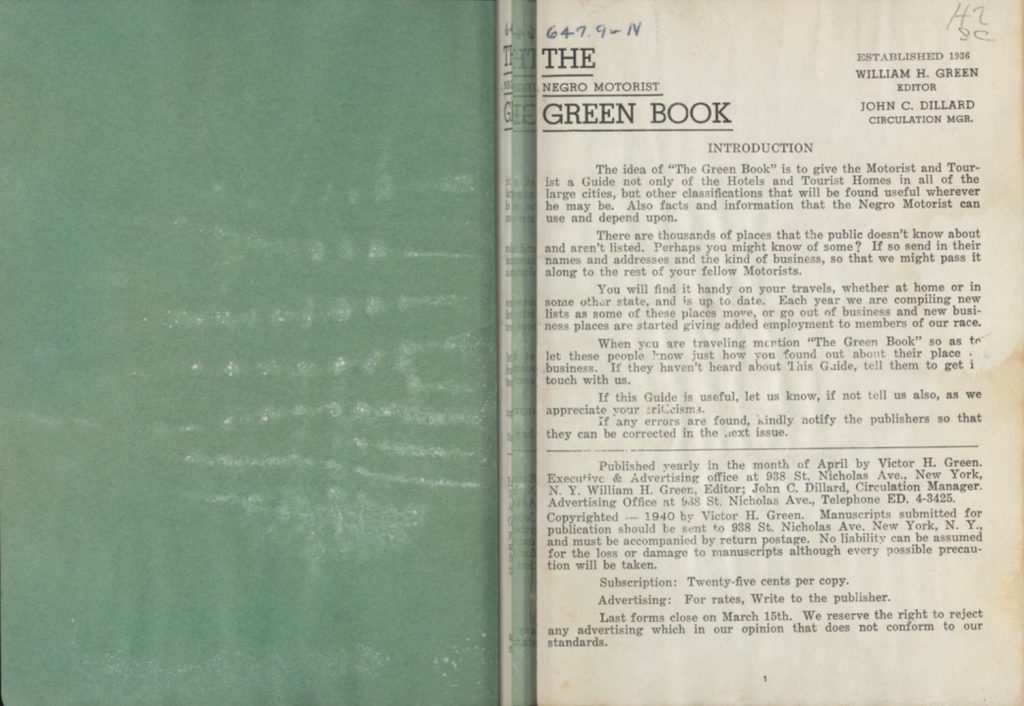

-Oddly, the film more or less skips over the entire importance of Victor H. Green’s The Negro Motorist Green Book — Van R Newkirk II (@fivefifths) on Twitter called it a “guide for escaping generations of actual terrorism” — detailing hotels, restaurants, barber shops, gas stations, night clubs and more that were “safe” for Black people. And not just in southern states (though there was little in NYC much below West 120th Street). For more info, take a look at the NY Public Library archived copies of actual Green Books and prepare to get lost in there.

-K. Austin Collins wrote The Truth about Green Book for Vanity Fair, and it’s become one of the definitive articles explaining the polarization — in particular, why this is a “based on a true story” picture that’s been sold and promoted as an actual true story, and why that’s problematic.

-Gabrielle Bruney in Esquire pointedly lays out how the 2019 Best Picture Winner “gets pretty much everything about racism in America totally wrong,” from inaccuracies about Dr. Shirley to the “bigoted undercurrent” of the suggestion that Dr. Shirley was more educated and refined than other Black Americans at the time, rendering him alien and isolated.

-In our post about where to stream the 2019 Oscar nominated movies, we linked to Monique Judge’s article in The Root that criticizes it as a white savior film with “palatable” racism that downplayed the realities of the south at the time.

Universal Pictures

Universal Pictures

-Brooke Oobie in a review for Shadow and Act, describes some of the film’s biggest challenges, the largest of which ia centering a Black person’s story on a white hero. “We don’t see Dr. Shirley’s story in Green Book without Lip’s lens,” she writes, and it’s a great point. You can even ask your kids how the story might have been told differently if it had been Dr. Shirley who narrated.

-Samara Lynn in Black Enterprise shares a scathing letter from Dr. Shirley’s only living brother, Maurice Shirley disputing a lot of aspects of the film, like the teal blue Cadillac and the famous fried chicken scene, but even more profoundly, the entire nature of Dr. Shirley’s relationship with Tony Lip. In fact, he states that the family was not even consulted about the film until after it was made.

-Finally, recommended by Brittany Packnett, this Vox piece by Todd VanDerWerff explaining quite clearly why Best Picture Academy Awards always go to “comforting fantasies” that make us feel like we can congratulate ourselves for helping put bad stuff behind us, even when it’s not. It’s more of a historical Oscars perspective from the POV of a film critic, and if you’re a film geek like me, it’s a really interesting read.

————–

None of this is to say you shouldn’t like Green Book. Or that you should feel guilty for liking it. There’s a lot that’s enjoyable about the film, including the stellar performances, and if there’s one description that seems to be consistent among all critics it’s that this is certainly a “feel-good film.”

But it’s really worth your time to consider why it made you feel good, if indeed it did.

Director Peter Farrelly used his acceptance speech to urge us to “look for what we have in common,” which is a perfectly lovely thought and overall sound advice. But I’d argue that it’s perhaps a more admirable goal to acknowledge what we don’t all have in common, and still be able to generate that same empathy, respect and kindness as we do for those who are more like us to begin with.

Fantastic Liz. Especially love your last paragraph. Truth.

Thank you Jeanine xo